The NLCHS has received Block Grant Funds to repair and paint the front porch of Historic Shaw Mansion. We are inviting contractors to bid on this project which should begin in July. Please click the link below to view the Invitation Letter and Work Description.

On August 13th,1779, Captain Daniel Waters and his crew abandoned the ship General Putnam along the Penobscot River and then set her ablaze. Once ashore, they began the long journey over land back to Boston. Putnam was part of a 44 ship flotilla tasked with driving the British from the Penobscot Peninsula in what is present day Maine. In a disastrous defeat, the American fleet was forced to flee four British frigates. One by one the American ships were either captured, destroyed, or abandoned and burned. Waters, a native of Charlestown, Massachusetts, was a seasoned military officer. Waters began service for his country as a Minuteman. One of the many who was roused by Paul Revere Lexington and Concord.

On August 13th,1779, Captain Daniel Waters and his crew abandoned the ship General Putnam along the Penobscot River and then set her ablaze. Once ashore, they began the long journey over land back to Boston. Putnam was part of a 44 ship flotilla tasked with driving the British from the Penobscot Peninsula in what is present day Maine. In a disastrous defeat, the American fleet was forced to flee four British frigates. One by one the American ships were either captured, destroyed, or abandoned and burned. Waters, a native of Charlestown, Massachusetts, was a seasoned military officer. Waters began service for his country as a Minuteman. One of the many who was roused by Paul Revere Lexington and Concord.

During the siege of Boston he commanded a small gunboat, and then was appointed the captain of the schooner Lee by George Washington in 1776. The General assisted Waters again a year later when he appointed the Charlestown man a captain the the Continental Navy. In the following years Waters captained the frigate Fox and the sloop General Gates. In 1779 Waters was given the Putnam after the ship had been pressed into service by the Sherifff of Suffolk County Massachusetts.

Dudley Saltonstall was the commodore of the fleet for the Penobscot expedition. In addition to the flotilla was a force of 1,200 men both marines and militia an, and 100 artillerymen under the command of Lt. Col. Paul Revere. Such was the failure of the expedition, but Saltonstall and Revere were tried before a court martial. Saltonstall was tried for ineptitude and declared incompetent. Paul Revere faced a number of charges, but was only asked to resign his command. His reputation smeared, Revere continued to ask for a full Court martial to clear his name. That finally occurred in September of 1783. The court convened and cleared the patriot’s name.

The lack of action was felt keenly by the all the forces during the expedition. Many of the officers complained to Saltonstall about his caution in moving the fleet. Even men aboard the ships chafed at the caution. A letter from the Putnam was sent to Saltonstall asking him to engage the enemy in polite and flowery terms. However of the 150 crew, the letter was only signed by the First Lieutenant and thirty others. Nor did Waters’ signature appear. The offensive dragged on until the reinforcements the British were waiting for arrived. August 12th 1779, found Waters fleeing from the British. Unable to escape after a day of sailing, the captain chose to abandon his ship and, burn the General Putnam to keep her from the enemy.

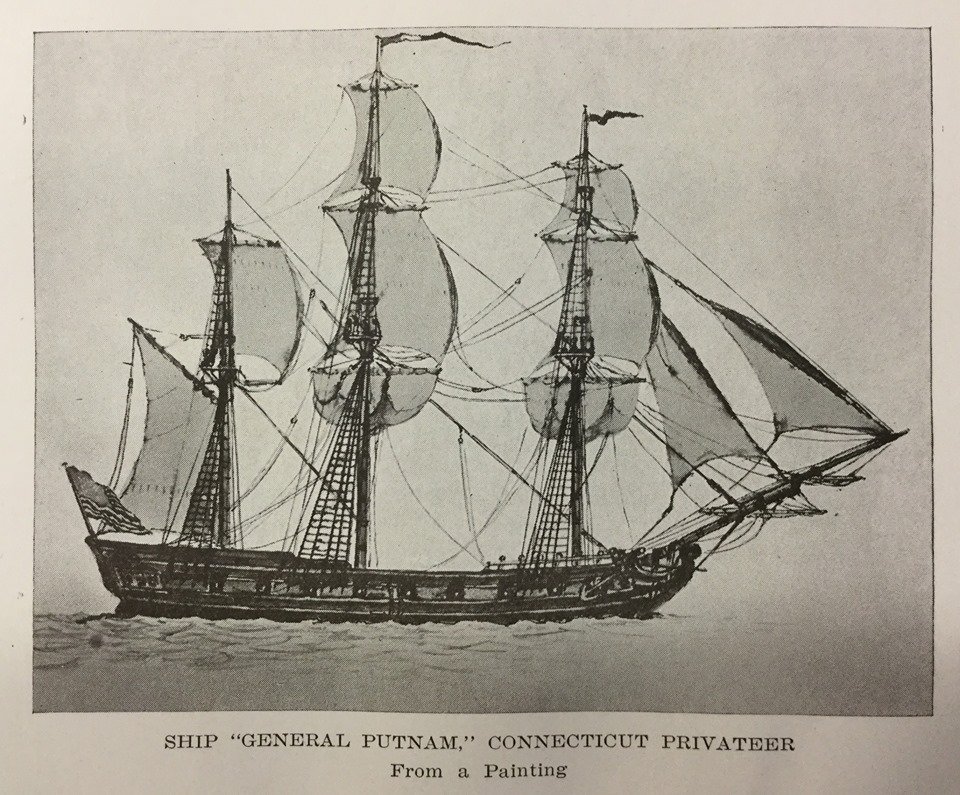

Two years prior to the disaster at Penobscot, Nathaniel Shaw Jr., began construction of a new ship at Windthrop’s neck in New London. She was a good sized vessel meant to carry a crew of 150. Shaw outfitted his newest privateer with 20 cannon, 9 pounders purchased in Norwich Connecticut. When she finally rolled down her stays, the General Putnam cost 50 thousand pounds to build. In 2020 that is approximately 8.25 million dollars. She was commissioned on April 23 1778, and got underway for her first voyage in May of the same year.

Thomas Allen of New London, a partner in the $10,000 bond for Putnam, was made captain for her maiden voyage. Shaw provided Allen with the following orders.

“NATHANIEL SHAW, Jr., & CO. TO CAPTAIN THOMAS Allen

Sir New London [Conn.] May 24. 1778 You are now Commander of the Privat[eer] Ship of Warr General Putnam, fitted & Man’d for a Cruize of Six Months against the Enimies of the United States, & now lying at Anchor in this Port, and our Orders to you are, That you Sail on a Cruize the first fair wind (after your Men are on board) a

nd Cruize where you think it will best Answere the desirable purpose viz. to take as many British Merchantmen Ships as you can Man, and send into the most convenient Port of the United States in America, should prefer New London, but if they fall into Bedford1 let the Prize Master apply to Joseph Russell Junr., if to the Eastward of that Port to Col Josiah Waters at Boston If to the Westward, Newbern to John W. Stanley,2 to the Westward of that to such Gen- tlemen as you think are Men of Honesty & Interest & that you can recomend as Such, & desire them to write me immediately, & dispose of Vessels & Cargo & let me know to what Amo. the prizes may have sold for, that we may draw on them for that sum We

wish you a Good Cruize and Safe Return to your Friends & OwnersNathel. Shaw Junr & Co.

A True Copy of the Original Thos. Allen”

It made sense that Shaw sent Allen to Boston, because the Captain had lived in the city prior to marrying a woman from New London. Allen cruised for 5 months and captured a total of 6 english brigs before returning to New London. Allen did not return to sea, but went back to managing his public house in the city.

Putnam sailed out of New London Harbor again in May of 1779 under the command of Nathaniel Saltonstall, brother of Dudley Saltonstall. Once again the privateer sailed the waters off the coast of Massachusetts. This time, however, Shaw gave orders that all captures were to be sent to New London and not to the port of Boston. Putnam captured three ships before encountering foul weather on the 26th of June, forcing her to anchor in Boston Harbor. Unfortunately on the 16th of June the British had landed a force to settle an area in Massachusetts on the Penobscot River. In addition to being a new settlement, New Ireland was to be haven for loyalists fleeing the colonies. In response to this incursion, The Massachusetts General Assembly appointed a Council of War to mount an expedition to drive the British from the Penobscot Peninsula. On July 2nd, 1779 the Council ordered the Sheriff of Suffolk County to press the ship Putnam into service.

Nathiel Shaw Jr. did not see any compensation for the seizure and destruction of the ship he had built. After arriving in Boston, Nathaniel Saltonstall was asked to give the ship over to the expedition. He declined feeling he did not have the right without the consent of the owners. The matter was decided by the Massachusetts Assembly. After the legislature authorized the pressing of the ship, Saltonstall was asked to assess her value. Again he declined. The Assembly appointed three captains to assess the ship. They determined her value value to be £10,000 sterling, with an estimate of future value at £100,000 paper money. It took until 1783 for the General Court to settle the matter. A year after Nathaniel Shaw Jr. died, the state of Massachusetts paid the Shaw company the sum of £10,133. 6s. 8d. in compensation for the loss of the privateer ship General Putnam.

In our collection are a selection of military artifacts owned by Lieutenant Colonel Thomas Wheeler of North Stonington. Thomas was born into the prominent Wheeler family in 1760 and was a cavalry officer in the Connecticut State Militia. He was commissioned as a Lieutenant in the Third Regiment in 1796 and, following subsequent promotions, ended up in command the regiment by 1805. It does not appear that Thomas Wheeler served during wartime, either in the Revolution or the War of 1812.

In our collection are a selection of military artifacts owned by Lieutenant Colonel Thomas Wheeler of North Stonington. Thomas was born into the prominent Wheeler family in 1760 and was a cavalry officer in the Connecticut State Militia. He was commissioned as a Lieutenant in the Third Regiment in 1796 and, following subsequent promotions, ended up in command the regiment by 1805. It does not appear that Thomas Wheeler served during wartime, either in the Revolution or the War of 1812.

Thomas Wheeler owned two matching brass, flintlock pistols. They were manufactured by Ketland and Co., a gun maker founded in Birmingham, England. Engravings and proof marks show that the metal fittings were manufactured and certified in London, likely in the 1760s. The handles are made of walnut, although it is unknown whether the wood is American or English, since gun parts were often shipped across the Atlantic to be assembled later in the Colonies.

Both feature half-octagonal brass barrels, a popular feature of many contemporary pistol designs. This was largely decorative, although the flat top would have assisted with sighting and the design would have provided extra reinforcement around the firing chamber. Additionally, an engraving of a rose decorates the bottom of both trigger guards, and just fore of these are two acorn-shaped finials. Both are common features on late 18th-century flintlocks, although any specific meaning of these markings has not been uncovered. Included in the collection are two fitted leather holsters for both firearms.

Thomas Wheeler carved his initials along the bottom of both barrels. However, Thomas was not their only owner, nor their first; both thumb plates are engraved with the initials “WW”. Our provenance notes for these artifacts do not list someone with these initials as an owner, so we must make an educated guess as to who the original owner likely was.

Thomas had a brother named William, who was a soldier in the Revolution. William Wheeler was a private in the 5th Connecticut Line Regiment and he died in service in February of 1778, likely at Valley Forge. However, as a private, it is unlikely that he carried two matched firearms of this craftsmanship.

On the Wheeler side, Thomas did not have any other direct relatives with the initials “WW”, but his mother had been born Martha Williams, of the Stonington Williams family. Thus, Thomas Wheeler had a grandfather, an uncle, and a cousin all named William Williams, and all three are possible owners. The latter is an interesting possibility; Major-General William Williams III was the Connecticut militia officer in command at the Battle of Stonington during the War of 1812. Thomas alternately may have acquired the pistols from another unknown source.

Another item of Lt. Col. Thomas Wheeler’s in our collection is his cavalry saber. The saber lacks any ornamentation or maker’s marks, but this Mameluke-style sword appears to be in the style of the British Pattern 1796 Light Cavalry Sabre, which would have been a fashionable choice for a new cavalry officer in the 1790s. Additionally, a set of Thomas Wheeler’s spurs are in our collection.

One interesting historical note for these artifacts comes from “The Stonington Battle Centennial”. It is mentioned that during the 1914 celebration of the Battle of Stonington, Benjamin Pomeroy Wheeler, Thomas Wheeler’s great-grandson, rode in the parade “carrying [an] old sword and pistols”. B.P. Wheeler left this name on a piece of tape on one of the flintlocks, and the sword mentioned is almost certainly Thomas Wheeler’s saber. This additional connection to the Battle of Stonington is an interesting correlation to the theory that Thomas’ cousin, Maj.-Gen. William Williams, had owned these pistols. Benjamin may have worn these to honor not only Thomas’ service, but also to reflect a family story that was not passed on when these items were donated in 1970.

These artifacts and their beautiful craftsmanship provide a window into the material culture of life and military service in Connecticut’s early statehood, and they draw questions about how family and those who had served were honored. Photo galleries of the two pistols, the saber, the spurs, and four military commissions, each signed by two governors of Connecticut – Oliver Wolcott and Jonathan Trumbull Jr. – can be viewed on the NLCHS website by following the link below.

With New London County Historical Society’s 150th Anniversary on the horizon, the board began considering the role of NLCHS within our community.

Founded in 1870, NLCHS is the oldest historical organization in eastern Connecticut and one of the oldest in the region. Headquartered out of the historic Shaw Mansion, NLCHS serves as stewards to a vast collection of cultural artifacts and archives.

With the next 150 years in mind, we are pleased to present our members and the community we serve with our new logo. This logo symbolizes our mission to preserve and share New London County’s rich history.

The logo represents two sides of NLCHS, our past and our future. As a nod to our forebearers, the blue and gold coloring are in honor of the Shaw family. The Shaw family were the original owners of the mansion, which has served as our headquarters since 1907. Blue and gold are the primary colors on the Shaw family crest, which hangs in our entry way. Secondly, the 13 starts represent the 13 original colonies, while the three larger star configuration in the center is another nod to the Shaw family crest.

Looking at the future of our organization the words Preserve, Educate, and Partner represent the three pillars of NLCHS. Through preservation, education and partnership with community-based organizations, NLCHS will continue to strengthen its ties within our community, and the region.

We’ve enjoyed serving our community over the last 150 years and look forward to the next 150.